You remember our plans on completing the Hilda baseline network to the nowthwest… ? – Yes, yes, Greenland.

Another year, another try – and this time with success!

Last Monday, Thomas and Konrad started again a trip to Greenland. This time, no Corona issues, perfect weather – and everything went smoothly and on time. After a great panoramic flight over nothwest Iceland and the Scoresby Sound, we finally make it to Ittoqqortoormiit, where we are greeted by Mette from Nanu Travel, who took care for our equipment through the Corona times.

While we had snow and rain in Iceland, Ittoqqortoormiit is still a winter wonderland. Meters of snow and ice, though the sun doesn’t set any longer. Temperature went up by 10 degrees since last week, so we are looking forward to comfortable consitions for setup – and plenty of woring time due to the Arctic day.

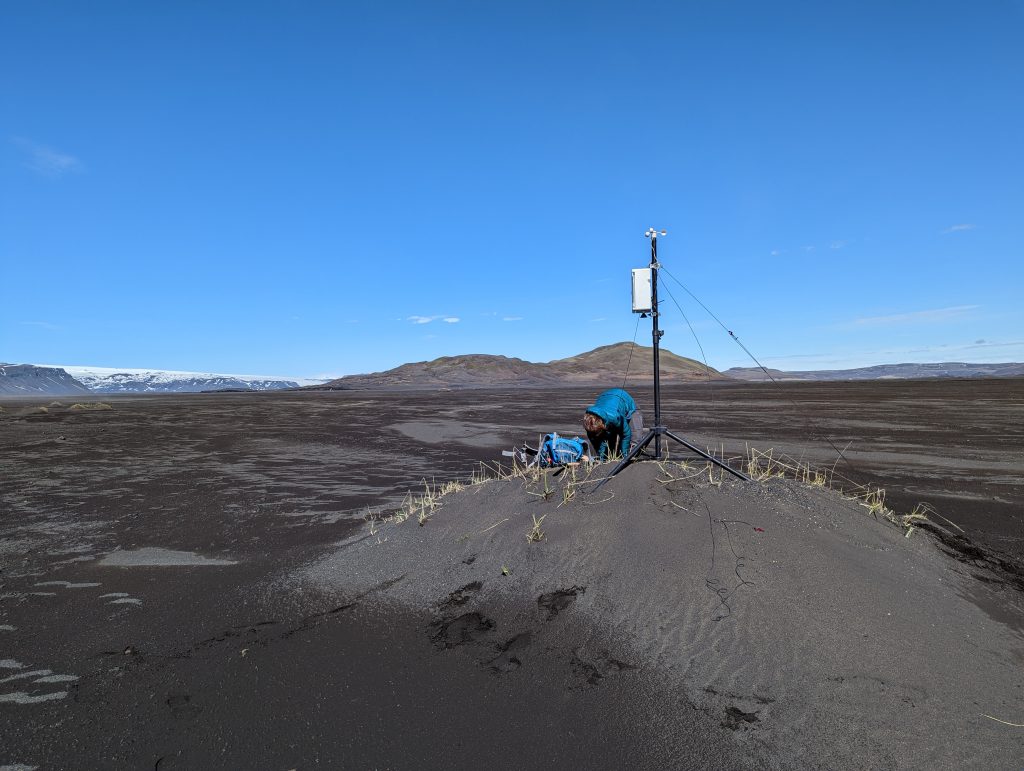

Next day we meet René and Hans from the radiosonde and telecom station up the hill, who will host our baseline measurement station for the time coming. After a short look around, we quickly decide for a suitable location and start unpacking our materials. Slowly, memories come back of the time two years ago – including the ones of all these undone things, as this station was the first one to be sent abroad. Unfinished mechanical works, an incompatible software system and non-existing remote control keep us busy for some days.

However, we have meanwhile gained a lot of experience, so it just takes time, until everything is done. Except for one thing: how to get the station online? It turns out that getting mobile data here for non-Greenlanders is close to impossible. After two days in search of possibilities, Mette saves us the day: we become commercial customers of the travel agency.

Now everything is in perfect order, so on Friday we switch on – and no more problems show up.

Konrad introduces our local caretakers in a great coffee-and-cake atmosphere to the sample handling procedures, so we can be confident that we will obtain interesting samples from this place.

Now, the Hilda network is at its maximum extension – alas, only for a few weeks.

Mýrar station will stop its operation after two years, as planned. When we finish the intensive observation period of this year in Iceland, we will take the first materials home again. Nevertheless, we have plenty of material to kep us busy in the lab for a long time!